When I interviewed for my first job (back in the 20th Century), the manager I was interviewing with had a wooden plaque on his wall. It said, “Change is great. You go first.” I thought it was funny at the time but later came to realize that plaque summed up corporate America’s view on change well. Most leaders know that they are supposed to recognize the need for change and to champion change. When it comes to doing something different however, they are resistant. Echoing the sentiment on the plaque, most are more than happy to let someone else go first..

We seem to be wired to resist change.

If we were in a group meeting right now, I would do a little change exercise to make the point. I would ask you to pair off and face your neighbor. Then to turn away, change three things about your appearance, and turn back. I would ask you to try and spot the changes your partner made. Then we would repeat the process.

During the exercise, people might take off their watch, button their top button, put up their collar, untuck their blouse, or even take off a shoe. After a couple turns at this, I would tell everyone, “Please sit down. We’re going to debrief.”

Being the insightful individual that you are, during the debrief you might have said that we’re generally happy with our appearance, and that changing it makes us uncomfortable. I’m sure you would have made other great comments, too.

Then I would ask you a question: “Are you are still wearing the changes that you made?”

Remember, I said, “Sit down” and not “Undo the changes you’ve made and sit down.” Every person I have ever done that exercise with reversed the changes. They all re-buttoned the top button, put the collar back down, tucked their blouse or shirt back in.

The changes that people made did not stick. Most times, that is what happens in real life too.

New Years’ Resolutions

For a New Years’ resolution one year, I decided I was going to start going to the gym before work. I met with a rep of the gym on January 3rd at 6:30 in the morning, the time I planned to work out.

The gym was pretty crowded, so I told the rep, “Listen, thanks for the info, but I’m not going to join. This place is just too busy, and I’ve got limited time before work”. His response was: “I’ll tell you what. If you join and you still think it is too crowded on February 3rd, I’ll give you your money back plus a $20 bonus. “

I took his bet and joined, and he was right. It was much less crowed four weeks into the year. He apparently knew the research. The number of people who keep their New Years’ resolutions drops to 75% after just one week. After a month, it drops down to 60%.

Not a great success rate. Even more surprising when we consider that resolutions represent important, desired changes that we came up with ourselves. No one imposed the change on us.

At the end of year, only about 7% of us will have kept our resolutions. We humans truly do seem to be resistant to change.

So, what’s going on? Are we and our organizations doomed to stay with the status quo, even when our brains know that we need to change?

The short answer is, there are ways to increase the probability of the change happening and sticking, but it’s not easy. One of the first people to conceptualize what happens during any attempt at change was social psychologist Kurt Lewin.

Unfreeze-change-refreeze.

Lewin’s model says that we need to think about change as a three-step process, illustrated below:

At the start, we’re frozen in our current state, the status quo, depicted by the ice cube on the left. We need to unfreeze things (melt the ice cube), then make the change, which is what pouring the water into the new mold is trying to show, then refreeze things in the new way. And voila, we get an ice ball instead of an ice cube.

The insight from Lewin’s model is that you can’t move directly from one solid, frozen state to another. Using the illustration, you can’t go from an ice cube straight to an ice ball. You must unfreeze the current state, make the change you want, and then re-freeze the change.

Organization change is even tougher.

An ice cube is simple; organizations are not. Just as individuals start in a frozen state, resistant to change and prone to slipping back, organizations are as well. Think of an organization effectiveness model like the McKinsey 7 S model. In that model, a well-functioning organization has all its components – Strategy, Structure, etc. – all in equilibrium. Any attempt at change will upset that equilibrium, and the system will “fight” to get back.

So, given that we have got both individual and organizational forces working against a change, what can we do?

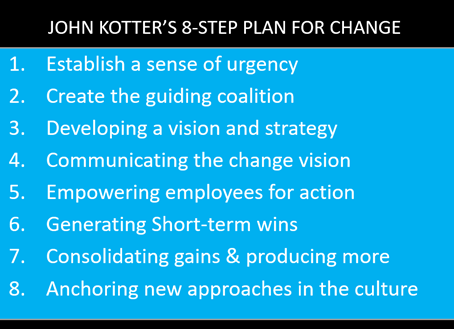

John Kotter wrote a book in 1996 called Leading Change. The illustration below shows his 8 steps. If you think back to Lewin’s model, Kotter’s first steps are about unfreezing – establishing a sense of urgency– the middle steps are about the change – communicating the change vision, and the last – anchoring new approaches in the culture — are about the refreezing.

Create a burning platform for change.

The first and by far the most important step in our experience is creating a sense of urgency; a compelling reason to change. This is sometimes called “creating a burning platform.” I heard that expression for years before I knew where it came from. If you do not, here’s the genesis of that phrase:

In 1988 an oil platform off the coast of Scotland caught fire and exploded. One hundred sixty-three people died. One of the workers who survived, Andy Mochran, jumped off the platform into the North Sea. A few facts: The oil platform was 15 stories high; the ocean was on fire from floating oil, and the North Sea is so cold that he could only survive about 15 minutes if not rescued. So, his jump was a jump to almost certain death.

When Andy was interviewed in the hospital, he was asked how he got up the courage to jump he, he said “It was either jump or fry.” He essentially chose almost certain death over certain death. In his mind, he had no choice. Organizational changes are typically not life or death situations, but the first step is making the case that we cannot continue the way we’re going, and we need to change now.

A pandemic unfreezing.

For years, employees pushed on management in many companies to allow more work from home. In 2019, one organization decided to address this (frequent) request from their corporate headquarters employees. The taskforce they assembled came up with good reasons to allow work from home. Those included less commute time, more flexibility for employees, better work-family balance, less distractions, built in resilience and back-up for emergencies at the office, etc. However, the taskforce found no compelling reason to change; no urgent, burning platform.

Not surprisingly, their recommendations were met with resistance from management. Managers cited challenges to collaboration, some workers not having laptops or high-speed connections at home. The IT department worried about security and hacking. The Legal department worried about liability and injuries at home.

Management recognized the value of making the change, but they also saw obstacles they would need to overcome. They did not see the cost-benefit in the effort required to make a “nice to have” change happen. So, the company kept the status quo. Fast forward ten months and the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Within weeks, all those objections – from IT to legal to management — were quickly addressed. Every employee in the corporate offices, up to the CEO began working from home. The change worked so well that the company cancelled their plans for a new office building.

Refreezing happens.

In this example, the COVID-19 lockdowns were an overpowering, compelling reason to change. Now, after more than a year has passed, the new WFH behaviors have been refrozen and we’re back on the left side of the Lewin model. Companies who think they can just re-open and bring everyone back with an email are in for a rude awakening. Businesses are finding that they once again must manage a change effort. Without a pandemic, and with over a year of success and satisfaction with WFH under their belts, it will not be a simple or easy change.

References

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Lewin, K. (1947). Group decision and social change. In: Newcomb T.M, and Hartley E.L. (eds) Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Henry Holt, 330–344.

Enduring Ideas the 7-S Framework (2008, March 1) McKinsey Quarterly. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/enduring-ideas-the-7-s-framework.